“Narratives provide us with the tools so sorely lacking in traditional forms of science communication,” says Prof. Wojciech Małecki. The researcher explores how narratives – literary and media – influence our attitudes and behaviour. He talks to Anna Korzekwa-Józefowicz about how a good story can attract attention and increase engagement, but also lead to unexpected outcomes.

Wojciech Małecki, photo Alina Metelytsia

Professor Wojciech Małecki – a literary scholar from the University of Wrocław – combines a humanistic approach with the tools of experimental psychology. He is interested in how stories influence our perception of the world.

Wojciech Małecki, photo Alina Metelytsia

Professor Wojciech Małecki – a literary scholar from the University of Wrocław – combines a humanistic approach with the tools of experimental psychology. He is interested in how stories influence our perception of the world.

- His first NCN-funded project explored how narratives shape people's attitudes towards animals and their welfare.

- He is currently examining how literature affects the way we think about climate change. Around 20,000 people from three continents will participate in the research envisaged by this project.

- He also conducts research on gender stereotypes in science – previously as head of a study involving 800 Polish high school students, and now as a member of an international team investigating these phenomena in academia.

Experiment with Matilda

Anna Korzekwa-Józefowicz: When we developed the Gender Equality Plan at NCN, I assumed that promoting women in male-dominated fields – and men in feminised fields – could help break down stereotypes and promote gender equality. In light of your research, is it an effective strategy?

Wojciech Małecki: Such activities, i.e. highlighting women's presence and achievements in science as a way of promoting equality, fall in line with well-known psychological theories, such as social learning theory or the so-called stereotype inoculation theory.

Our experiment showed that the impact of such messages can be more complex than is usually assumed. A few years ago, we conducted a survey among high school students in which we wanted to find out whether these kinds of messages really affect the attitudes of the audience.

There are many programmes in operation today aimed at breaking stereotypes and encouraging women to choose science and technology, so we were interested to see what effect they actually produce. We also wondered whether the effectiveness of such messages depends on the field – will there be different effects in feminised areas as compared to those where women are still very scarce.

As part of the experiment, we examined whether highlighting women's contributions to a given field – in our case, mathematics, psychology, philosophy and biology – could increase high school girls' motivation to pursue these areas and strengthen their interest. It turned out that messages explicitly stating that women made the described discoveries had the opposite effect than assumed – they discouraged both girls and boys from engaging in the given field. They also made the area in question seem less interesting.

How did you check the impact of such messages?

In each of the fields analysed, we created three versions of narratives about important and interesting scientific achievements: one in which they were attributed to women, one in which they were attributed to men and a third – a neutral one, without indicating the author – where only the research outcome mattered.

Unfortunately, it was the versions with female scientists as protagonists that proved least effective – they evoked less interest in the field and proved to be discouraging.

We called this result the Reverse Matilda Effect. The classic Matilda Effect refers to a situation where – if a given field is valued and prestigious – women's contributions to its development are often diminished, overlooked or entirely erased. There are many historical examples of this phenomenon, especially in the context of awarding prizes. The most famous is the story of Rosalind Franklin, whose breakthrough data, according to various experts, enabled the discovery of the structure of DNA, but it was Watson, Crick and Wilkins who received the Nobel Prize for this discovery.

In our study, we are dealing with the opposite: whenever women's contributions are explicitly highlighted, the field begins to be perceived as less important, less prestigious. That's why we called it the Reverse Matilda Effect.

This was surprising, yet on the other hand, there are data showing that as a profession feminises, wages in it unfortunately decline. In other words, when women's participation increases, the social valuation of this work often decreases.

So, does this mean that such campaigns are basically a waste of time?

On the contrary. This serves as an argument for more and more comprehensive campaigns to promote women's participation in science. We are like the crew of a ship sailing across the ocean that must be rebuilt while still at sea. We don’t abandon it but rather transform it – refining and improving what already exists.

Our research – or at least our interpretation of its results – suggests that there are still deeply rooted beliefs about who can be perceived as a “good scientist”. There is a clear discrepancy here between the stereotype of the scientist and the stereotype of the woman.

On the one hand, we have the image of the scientist as a cool, rational, analytical person – an objective mind. On the other, there is the stereotype that psychologists refer to as women are wonderful, that is, of women as empathetic, emotional, caring people. And it just doesn't add up for people.

When someone hears that it is women who are successful in a field, and this does not fit the established image of the scientist, they may start to question the significance of the field itself. They might start to see it as less serious, less scientific – reflecting existing stereotypes rather than the actual value of the discipline. This is a very troubling mechanism.

If emphasising gender can have unintended consequences, perhaps it's better to focus solely on the discoveries themselves? But then, how do we avoid women disappearing into the shadows once again?

First, it's still crucial to highlight women's contributions to science. For years, these contributions were simply erased and that's not an opinion, but a fact. Acknowledging this is the first step. Secondly, we need narratives that showcase diversity and challenge established patterns. Without this, it is easy, even in good faith, to reinforce the belief that men are the “natural” leaders in science, with women in supporting roles.

It is important that such messages reach the youngest audiences, at an early stage of education. Children should see women active in science, successful and present in the public space as experts.

It is also important to remember that high school students constitute a very specific group, so conclusions should not be drawn for the whole population. The results of this study show only a piece of reality. Similar messages may be perceived differently in other groups.

You are now involved in similar research in academia. How do the results differ from the earlier research?

Our research involved hundreds of people from different countries and continents: female students, male and female PhD students and female researchers. Only a comparison of the results from different environments will allow for a better assessment of whether we are also dealing with a similar mechanism here.

It may be assumed that reactions in academia will be different – primarily because awareness of the existence of bias against women in science is significantly greater here. Students and doctoral students know that the problem of inequality still exists, and stereotypes still influence the functioning of science; for instance, in recruitment processes or in the representation of women at conferences, especially among plenary speakers. Thus, it can be expected that messages highlighting women's contributions to a given discipline will be received differently in this environment than by high school students, who do not yet possess the knowledge or tools to recognise and counteract such mechanisms.

Are there campaigns that you, from the perspective of a researcher and a citizen would consider well designed?

I can say that I have not seen any that appear completely missed. There are many examples, particularly in the United States, where there are activities targeted at the youngest audiences. And these are truly necessary initiatives. It is also worth remembering that, in addition to campaigns, there are major scientific projects that aim to complete the history of particular disciplines – so as to restore the memory of women's contributions. These activities are equally important.

Fiction stronger than the graph?

In your first NCN project you analysed the impact of narratives on attitudes towards animals, and now on attitudes towards climate change. Can literature influence the way we think about our planet?

Communication sciences and media psychology increasingly emphasise that traditional ways of communicating scientific information, such as statistics or dry descriptions, have limited impact. That’s why there is a growing interest in more engaging forms – such as narratives: stories and literary works, but also video games, films and series. These types of messages, concerning climate change, among other things, are present in many media today and, as research shows, are really necessary.

Is a fictional story more persuasive than data, figures or a report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change?

Narratives help to deal with one of the key problems of climate communication, i.e. the lack of attention. Many people are not interested in climate change for various reasons. Some do not believe in it, and some, even if they recognise it as a real threat, do not see it as something that affects them directly. Psychologists speak here of a “limited resource of concern”: each of us has a limited amount of attention that we can devote to worrying about various things, so we tend to focus on what concerns ourselves, our environment and the immediate future. And climate change often fails to meet these criteria. That's why we're more worried about a broken phone than extinction of species.

Notably, each of us knows this mechanism from our daily experience – if we want to stop worrying about something, the most effective method is to find an even bigger worry. But seriously now, there are studies that confirm the limited pool of worry effect in the context of climate change. We see that when there is a major social problem – such as the economic crisis in 2008 or a pandemic – the level of public concern about climate change drops. Attention shifts to where a new, more absorbing threat has just emerged. There are, for example, interesting analyses that have shown how the number of mentions of climate change on Twitter decreased as the number of posts about pandemics grew.

Narratives, including fiction, but also other forms of storytelling, can help us because they have a remarkable ability: they can literally make any subject fascinating, no matter how boring or daunting it would seem in another context. If something is told in an attractive narrative form, it gains a whole new dimension.

We have plenty of examples in the literature. Proust, for example, who made the madeleine-eating scene something that has fascinated millions of readers for decades. And exactly the same can be done with topics such as climate change.

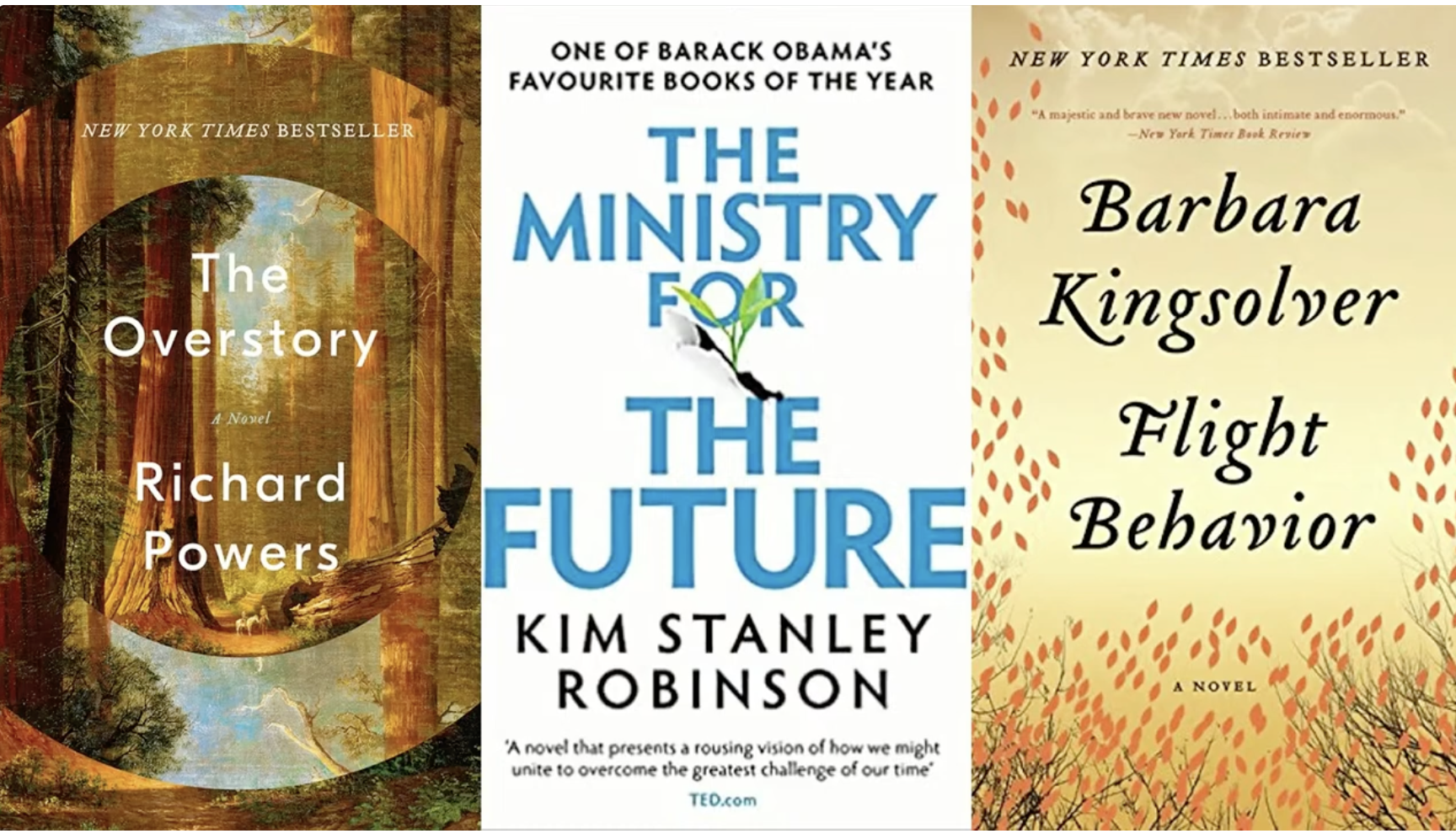

The classics of this literary trend include The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson, Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kingsolver and Water Knife by Paolo Bacigalupi. Will these books change our relationship with the planet?

The Water Knife is one of my favourite examples. It is an internationally successful, award-winning sci-fi thriller with climate change and its impact on water access in the southern United States at the centre of its plot. It is a book read by thousands, perhaps millions of people, many of whom probably had no interest in climate at all before. But thanks to this narrative form, the topic became engaging and understandable for them.

This shows that narratives can overcome the first, fundamental problem of climate communication, i.e. the lack of attention.

And is that enough?

There's also a second aspect in which narratives prove exceptionally helpful. Broadly speaking, it is a deficit of imagination. Even if we do manage to get someone interested in climate change, we still have trouble imagining it in specific, sensory terms.

Climate change is a complex process occurring simultaneously on the macro and micro scales – global temperature changes, local weather events, changes in the functioning of ecosystems or individual organisms. They are very difficult to grasp through experience. You can see this, for instance, on social media: all it takes is a winter storm in one part of the world for someone to ironically comment, "There you go, there's your global warming”.

Evolutionary psychologists point out that we are not biologically equipped to think in terms of either very large or very small scales. Our imagination works best with “medium-sized” objects: trees, chairs, people. This is why it is so difficult for us to understand astrophysics or quantum physics, for example. Colloquial language is not enough; we have to resort to the language of mathematics to convey the complexity of these phenomena.

And this is precisely where the role of narratives emerges. They can translate complex processes into concrete events and images. Narration allows you to “experience” the process in question, to empathise with the protagonist's situation, to get close to their experiences. In this way, we can indirectly experience, for example, the monstrous heatwave in India, as described, for example, in The Ministry for the Future.

This is something that conventional scientific discourse will not provide. And that's precisely why I focus on narratives – they give us tools that are so desperately missing in traditional forms of scientific communication.

Covers of selected climate change novels

Which of these classics in particular allows you to “experience” climate change?

Covers of selected climate change novels

Which of these classics in particular allows you to “experience” climate change?

Among those I've read myself, I'd definitely emphasise The Ministry for the Future. This novel is part of the debate about which narratives are more successful: apocalyptic or utopian. Typically, catastrophic stories dominate, as it's much easier to grab an audience's attention by showcasing dramatic events, apocalypse or dystopia.

Writing convincing utopias is much more difficult because it requires presenting a whole range of concrete solutions: political, economic or technological. This can often be tedious and difficult to show in an attractive way. Kim Stanley Robinson, however, has managed this brilliantly, skilfully dosing the catastrophic and positive elements. The novel begins with a description of a monstrous heatwave in India that claims millions of victims. Critics emphasise that this chapter hits like a punch in the face – incredibly powerful, even stunning.

In the following sections, the author presents a series of global and local changes that lead to positive outcomes. Importantly, once again, this is a matter of narrative – we observe all these processes from the perspective of the people whose stories emotionally engage us. These changes are tangible, portrayed through the eyes of the characters we root for. The entire narrative takes the form of a dynamic, energetic manifesto. It makes you want to get up and do something.

And Robinson achieves all this in one book of around six hundred pages. For me, this is a model example of how to create effective narratives.

The assumption about the impact of literature has one rather fundamental limitation – the alarmingly low level of readership, at least in Poland. The National Library data shows that almost 60 per cent of us did not read a book last year.

Climate fiction is one of the hottest, nomen omen, literary trends today. Novels of this type win prestigious awards, are translated into many languages and are highlighted by literary critics, politicians and opinion leaders. One example is Richard Powers' Letters, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. This is a really important trend that deserves to be highlighted.

And when it comes to readership, of course, certain forms are losing popularity, but new forms are taking their place. Just look at the development of independent publishing platforms. The book market is still functioning; there are many bestselling authors. Moreover, when discussing the impact of literature, not only the number of readers matters, but also who is reading. Consumers are often people with important social roles – teachers, educators, people of culture. Even if the audience is narrow, its impact can be significant. Intuitively, although I don't have hard data to back this up, I would say that such people take this content further, reaching a wider audience. Therefore, when it comes to literature, I remain cautiously optimistic.

It must be added, however, that the mechanisms we explore in the context of literature also apply to other narrative forms. Our results can in all likelihood also be applied to other media – films, series, audiovisual narratives. And in their case, no one doubts anymore that they reach a much wider audience.

You mentioned that Kim Stanley Robinson's book is 600 pages long, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour is not much less. The audiobook I listened to lasted almost 17 hours. How do you find readers?

Normally, the impact of whole novels is not studied; this would prove experimentally impossible. We use extracts from novels or short stories. In doing so, we assume that the effects of reading the entire book would probably be even stronger, as longer contact with the text tends to increase the impact of the message. This method is standard.

We conduct research online, using special platforms that provide access to research panels from many countries.

We run them in Poland, the US and India. One common limitation of communication research is its focus on Western populations. We are trying to remedy this by conducting experiments with populations from the Global South, where there is still relatively little such research.

How does such an experiment work?

For example: in one part of the project, we address a question that is widely discussed in climate communication research – what kind of emotions should accompany such messages? Does a fear-based message – for example, apocalyptic visions of the future – work better, or rather a message based on hope, showing a positive goal and the way forward? There are arguments on both sides. On the one hand, it is said that fear can mobilise, but on the other, it can paralyse, exacerbate climate anxiety and deprecate mental health without leading to real changes in behaviour. On the other hand, a positive message, focused on hope, also rises concerns: it can create a sense of complacency, a mindset of "everything will be fine", so nothing actually needs to be done.

There are other methods of studying the impact of narratives – those concerning behaviour. For example, participants receive a certain pool of funds that they can distribute among various NGOs, including those working on climate protection. This makes it possible to check whether a given narrative translates into real decisions rather than just declarations.

We determine the size of the sample using statistical methods, which ensures that the survey has adequate power. This allows us to determine precisely which narrative produces a stronger impact, under what conditions and with what effect.

And how are the people selected for such a study?

Our project is based on an assumption that currently dominates climate communication, which is that there are different audience segments with different attitudes towards climate change, so messages should be tailored to the specifics of these groups. Here we use a classification developed by researchers at the Yale Climate Communication Center, known as the “Six Americas”. These researchers distinguish six types of audience: from those who are very concerned (“alarmed”) to those who reject climate change altogether.

In the experiments on utopian and catastrophic narratives, we were particularly interested in respondents from the “alarmed” and “concerned” groups, as these are the groups concerned about the climate, but their real activity in this regard is relatively low.

Is it confirmed then that an indirect message is the most effective, i.e. a combination of a narrative indicating a threat and an optimistic message?

Yes, we have confirmed a hypothesis consistent with what is described by the so-called Extended Parallel Processing Model. It points out that the best persuasive effects and the greatest motivation for action are achieved when the narrative contains both negative and positive emotions. In other words, it is more effective to integrate the element of a threat with hope than to use only a catastrophic vision or utopian “hopium”, a kind of an opium of hope.

#NCNInterview

We have recently discussed research and research career with Karolina Zielińska-Dąbkowska, architect, Krzysztof Szade, biochemist Zuzanną Świrad, geomorphologist, Anna Matysiak, demographist and economist and Różą Szwedą, polymer chemist.

The interview was originally given in Polish and later translated into English by a third-party translator.