417 projects will be funded under the recently concluded OPUS 21 call. Among these, many set out to study ancient civilizations that have shaped the landscape of our modern world.

The art of debate

Polemics and debates have accompanied humanity from time immemorial; hate and fake news are far from new inventions that just appeared in the digital era. Even the first poets indulged in an occasional verbal skirmish that would probably be labelled as hate speech today. For spectators who watched ancient theatre plays, invective was the order of the day. More interesting still are the disputes that have survived, not only between literary characters, but also actual people, who spoke out in courts and the agora, wrote letters and poems. Importantly, uses of insult and “hate speech” techniques were even taught in schools.

Honoré Daumier – Achilles vs. Agamemnon

“Even St. Jerome ridicules the heretic Pelagius, suggesting that he got himself “stuffed with Irish porridge” in his youth, and mocks “Vigilantius” (literally: “awake”), arguing that he is a sleepyhead and a slow thinker and would thus be more fittingly called “Dormitantius” (“asleep/sleepy”)”, says professor Rafał Toczko from the Nicolaus Copernicus University. The scholar will carry out a project entitled “History and rhetoric of the invective in ancient Greek, Roman, and early Christian polemics”, which was awarded nearly PLN 724,000 in funding. He will examine and describe the polemical uses of invective between the 7th century BCE and the 5th century CE. The study is meant to collect and analyse the uses of the device in disputes between living (and not literary) interlocutors. “If the project succeeds, it will be the first such comprehensive study on classical and Christian antiquity. We will use text-search software to look for specific phrases and grammatical forms”, Toczko explains.

Honoré Daumier – Achilles vs. Agamemnon

“Even St. Jerome ridicules the heretic Pelagius, suggesting that he got himself “stuffed with Irish porridge” in his youth, and mocks “Vigilantius” (literally: “awake”), arguing that he is a sleepyhead and a slow thinker and would thus be more fittingly called “Dormitantius” (“asleep/sleepy”)”, says professor Rafał Toczko from the Nicolaus Copernicus University. The scholar will carry out a project entitled “History and rhetoric of the invective in ancient Greek, Roman, and early Christian polemics”, which was awarded nearly PLN 724,000 in funding. He will examine and describe the polemical uses of invective between the 7th century BCE and the 5th century CE. The study is meant to collect and analyse the uses of the device in disputes between living (and not literary) interlocutors. “If the project succeeds, it will be the first such comprehensive study on classical and Christian antiquity. We will use text-search software to look for specific phrases and grammatical forms”, Toczko explains.

The project will help create an online Database of Ancient Invective, containing all the instances of its use in ancient public discourse, i.e. in speeches, letters, pamphlets, treatises, and sermons. “We will be able to look up and compare the kinds of invective used by different authors, search for specific categories, such as animal metaphors or sexual allusions. We will also be able to see who these insults were levelled at and how the portrait was painted”, says professor Toczko. All these resources can later be used by social scientists to draw more general conclusions about the uses of invective in different cultures and periods. This can also be of interest to the general public, especially in our era, where insults, insinuations, and innuendos spread through the public discourse like wildfire.

“Today, politicians do not need to directly slander one another; they will have a crowd of journalists, internet users, and hired trolls to do that for them. In antiquity, the best you could do was publish your particularly scathing invective anonymously, a tack used by Cicero in his political struggle with Marc Anthony. Would the ancients be civilized by observing our current public debate? I doubt that”, speculates Toczko.

Religion and the material world

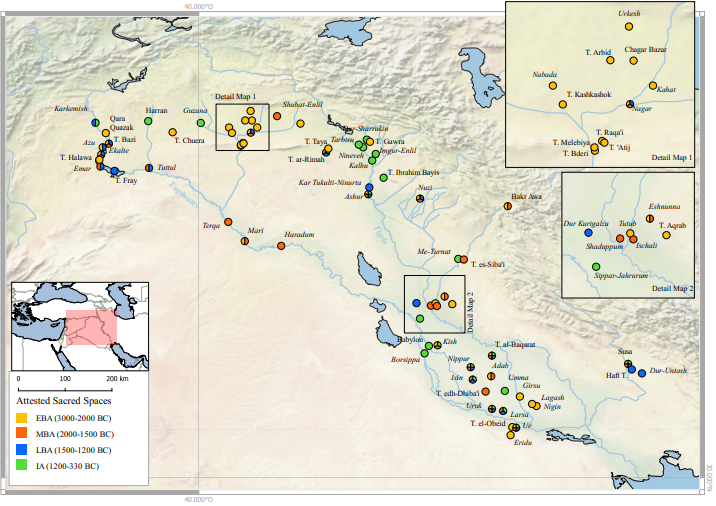

Map of confirmed temple sites in Mesopotamia

Religion has been an important element in all civilizations around the world and the way it is experienced has always aroused wide interest. Dr Christina Tsouparopoulou from the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences studies the phenomenon as it evolved in various communities of historical Mesopotamia (contemporary Iraq, north-eastern Syria, and neighbouring regions) over several millennia. Entitled “Material religion of Mesopotamia: a shifting landscape of relationships between gods and humans in ancient Mesopotamia”, her project was awarded nearly PLN 1.4 million in funding.

Map of confirmed temple sites in Mesopotamia

Religion has been an important element in all civilizations around the world and the way it is experienced has always aroused wide interest. Dr Christina Tsouparopoulou from the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences studies the phenomenon as it evolved in various communities of historical Mesopotamia (contemporary Iraq, north-eastern Syria, and neighbouring regions) over several millennia. Entitled “Material religion of Mesopotamia: a shifting landscape of relationships between gods and humans in ancient Mesopotamia”, her project was awarded nearly PLN 1.4 million in funding.

Tsouparopoulou emphasizes that “religion is a continuous and evolving process”. “The goal of the project is to take a closer look at how religious practices have changed over centuries. In particular, we will focus on around 3000 years of evolution and change in the religious practices of Mesopotamia”. She plans to combine an innovative theoretical framework with concrete, data-driven analytical methods. This will allow her to recreate the forms of human-divine relationship and cultic practices in the living landscape of the ancient past. Tsouparopoulou’s is the first project thus far to harness digital humanities, archaeology and statistical analysis for the study of cultic practices and attempt to reconstruct the human-divine landscape of Mesopotamia. “We will cooperate with other researchers and employ digital humanities and social network analysis to create models of relations between man and god”, explains Tsouparopoulou. These will not only shed light on the personal religious experiences of ancient Mesopotamians, but also link them to a broader context, which changed in step with the social and political vagaries of local and regional communities.

Tsouparopoulou also puts an emphasis on the role of open access in her research. “It is our duty as researchers to get people involved in what we do. Open access is of key importance for this project and the region it studies, since it helps to preserve an important aspect of the cultural heritage of a region that was under serious threat not so long ago, and makes it accessible to all”, she says.

“Mesopotamia was and continues to be a region with a very diverse population, which has handed down to us countless texts, artefacts, and buildings that paint a fantastic picture of everyday life. This makes it particularly interesting to study”, she sums up.

Heritage on the verge of disappearance

Paintings in Atico recorded in 2019

Successful projects also include one entitled “Atico Valley – Peru before Columbus. Development and intercultural relations between the mountain and desert communities of southern Peru”. Professor Józef Szykulski from the University of Wrocław was awarded nearly PLN 2.7 million in funding and will carry out his research on the northern tip of Peru’s Costa Extremo Sur, an area of intersection between the cultures of Paracas and Nasca in the north and the cultures of the southernmost strip of the coastline, situated south of the Atico Valley. Despite its location, the Atico Basin is still a pristine region in terms of archaeological research. “The project is an interdisciplinary endeavour and brings together a diverse team of specialists. We will have archaeologists of various stripes, experts on ancient DNA or genetic analysis of human remains, physical anthropologists, as well as experts on geology and topography”, the scientist underscores.

Paintings in Atico recorded in 2019

Successful projects also include one entitled “Atico Valley – Peru before Columbus. Development and intercultural relations between the mountain and desert communities of southern Peru”. Professor Józef Szykulski from the University of Wrocław was awarded nearly PLN 2.7 million in funding and will carry out his research on the northern tip of Peru’s Costa Extremo Sur, an area of intersection between the cultures of Paracas and Nasca in the north and the cultures of the southernmost strip of the coastline, situated south of the Atico Valley. Despite its location, the Atico Basin is still a pristine region in terms of archaeological research. “The project is an interdisciplinary endeavour and brings together a diverse team of specialists. We will have archaeologists of various stripes, experts on ancient DNA or genetic analysis of human remains, physical anthropologists, as well as experts on geology and topography”, the scientist underscores.

Another successful scientist, professor Błażej Stanisławski from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, PAS, will carry out a project entitled “Archaeology of the seascape of the Constantinople port in the Kucukcekmece Basin – land and underwater research, communication and trade networks, mobility”, which was awarded a grant of more than PLN 769,000. The goal is to study the largest port of Constantinople, which operated between the 6th and the 14th centuries. That it was indeed quite big is evidenced by the fact that its size was larger than that of all other known Constantinople ports put together. The study will follow the principles of so-called ‘seascape archaeology’, a field of research that examines relations between humans/culture and the sea. Professor Stanisławski’s project is also important from the point of view of conservation. The scheduled construction of the “Istanbul Canal”, which is to link the Marmara Sea and the Black Sea, means that the research site, which is located in the investment area, will have to be taken down in a few years. As a result, this is the last and only chance to study this amazing relic of civilization.

Dr Anna Józefowska-Domańska from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, PAS, will stay in Poland to conduct her project entitled “Consumption and ritual in the early Iron Age on the example of the settlement of Milejowice and the Domasław necropolis. Between the function and meaning of »ceramic collections«”. The researcher won a grant of PLN 442,000. She will work with a team of researchers specialized in excavations, as well as botanical and chemical analysis, to examine the importance of old ceramics, complementing European studies with new data and innovative guidelines. For this purpose, the team will use artefacts found at Lower Silesian sites during archaeological rescue research conducted along the construction strip of the A-4 highway. Identifying the role of these vessels is an important source of information for the study of customs related to food consumption and processing, as well as relationships between dietary habits, status, and identity within these societies.

The OPUS call is open to researchers at all levels. To serve as a principal investigator under an OPUS project, applicants do not need to hold a PhD degree but must document at least one published research paper (or one that has already been accepted for publication), or one achievement in art or art and research. The grant may go toward funding projects carried out by teams affiliated at universities, PAS institutes, scientific libraries or industrial research centres, including projects that use large international equipment or involve foreign partners. OPUS 21 ranking list.