An international team of astronomers, among them researchers from the OGLE sky survey run at the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw, as well as from the Gaia Alert System, announced in Science the discovery of a new class of exoplanets: free-floating planets. Research was co-funded by the National Science Centre.

Free-floating planets are objects that roam the Milky Way on their own, not gravitationally bound to any star. The discovery was made possible by directly “weighing” a planet detected through a phenomenon known as gravitational microlensing, designated KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516. Its mass is estimated at about 70 times the mass of Earth.

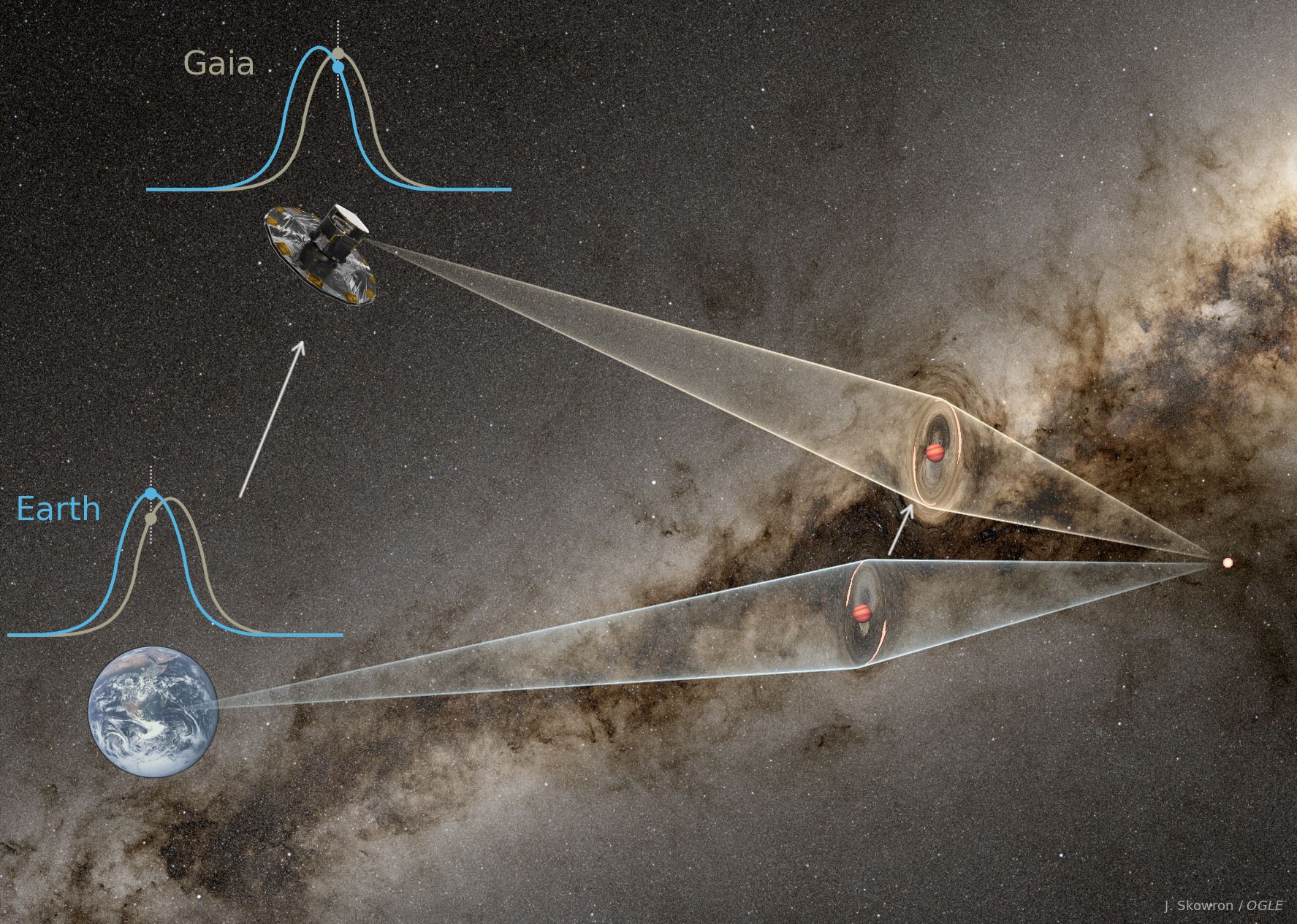

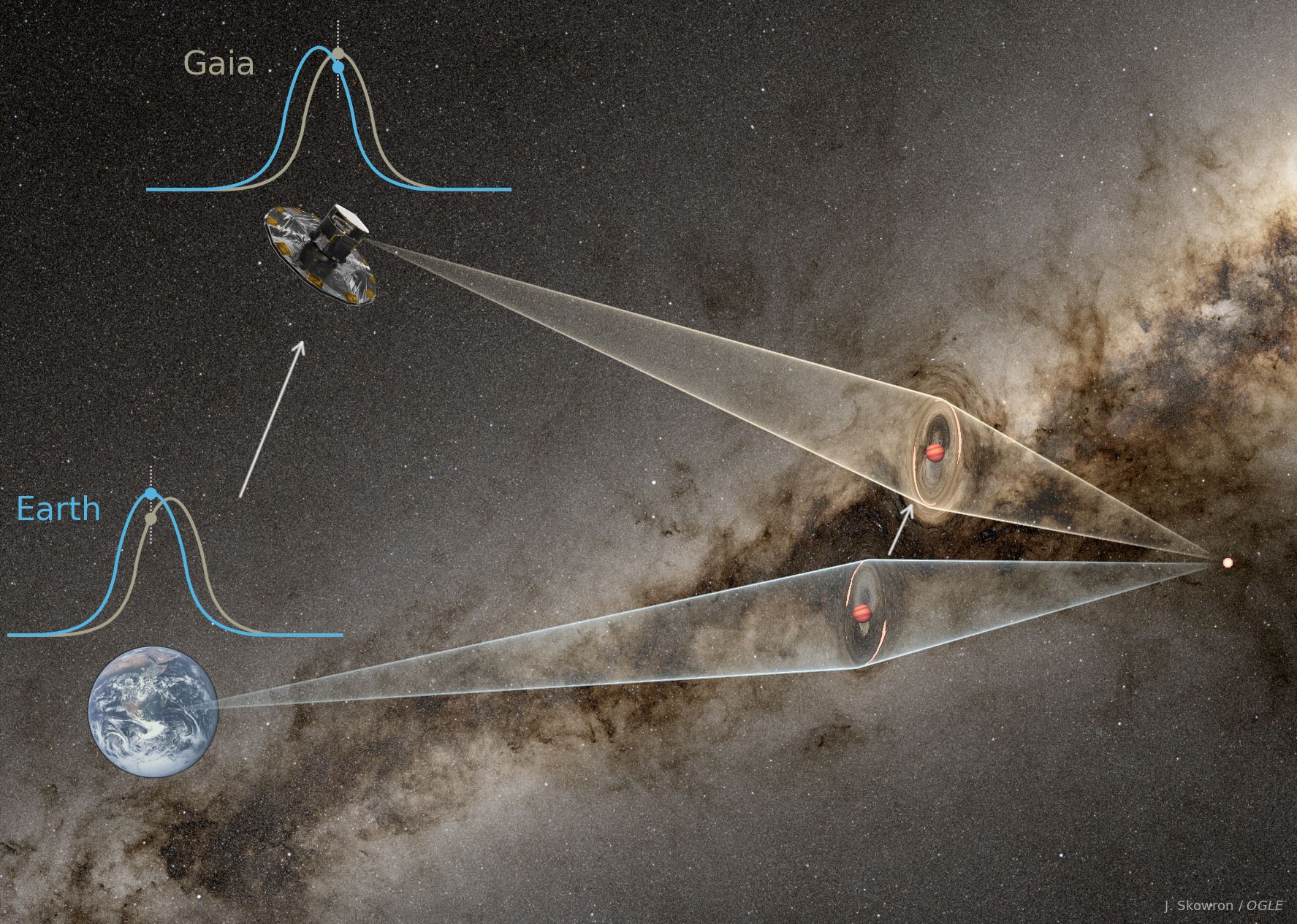

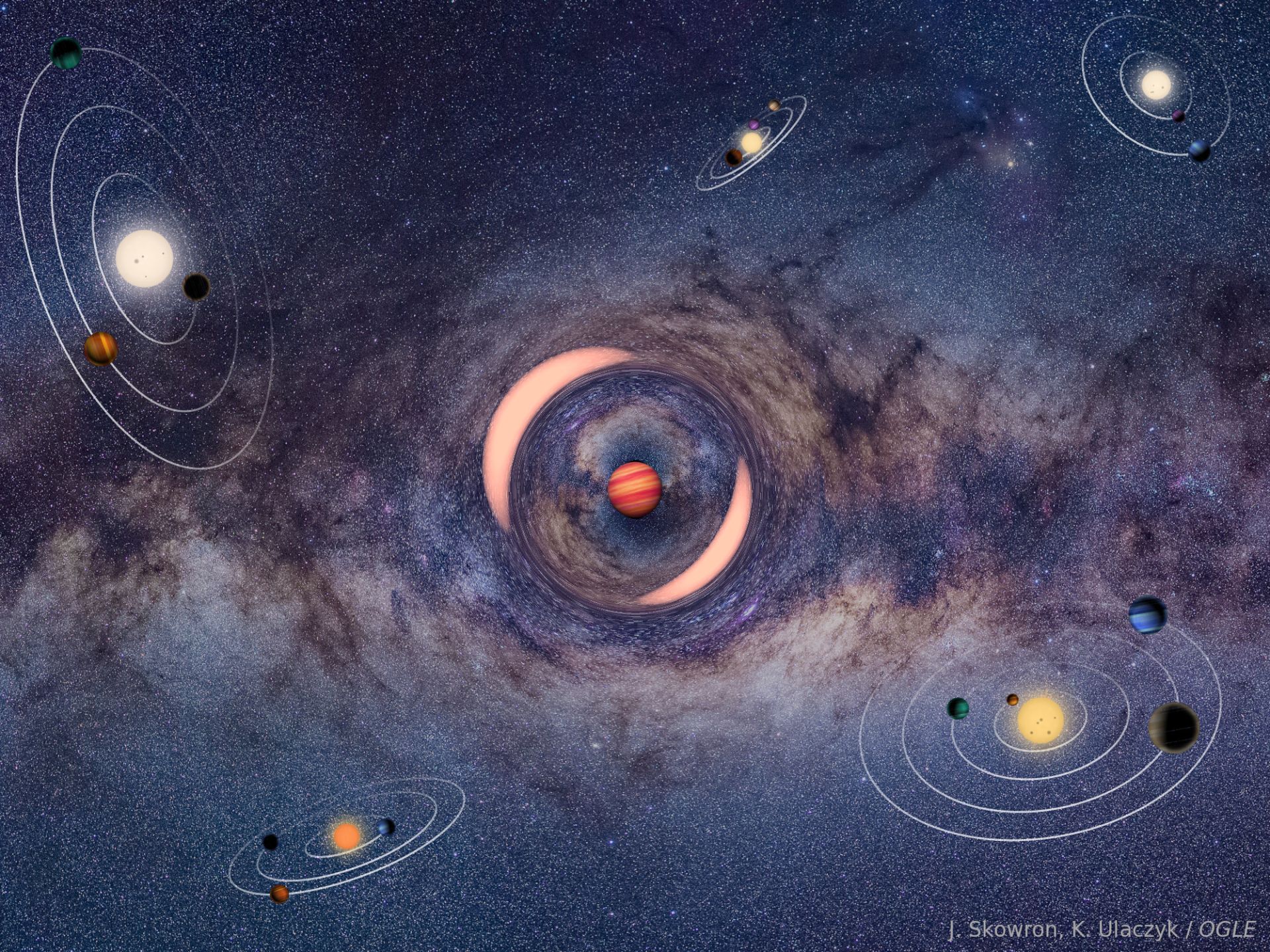

Artist’s impression of the microlensing event KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, observed simultaneously from ground-based observatories and by the Gaia satellite. Credit: J. Skowron / OGLE

The possibility of worlds beyond Earth, or even extraterrestrial civilizations, has fascinated humanity for centuries. However, it was only about 30 years ago that the first planets orbiting Sun-like stars were discovered, giving rise to a new field in experimental astronomy: the study of exoplanets. Over the past few decades, this field has developed at an astonishing pace, revealing ever more secrets of alien worlds and demonstrating that our Solar System is just one of many planetary systems in the Universe, and not necessarily a unique one. Until now, however, all known exoplanets were found in systems gravitationally bound to their host stars, orbiting around them.

Artist’s impression of the microlensing event KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, observed simultaneously from ground-based observatories and by the Gaia satellite. Credit: J. Skowron / OGLE

The possibility of worlds beyond Earth, or even extraterrestrial civilizations, has fascinated humanity for centuries. However, it was only about 30 years ago that the first planets orbiting Sun-like stars were discovered, giving rise to a new field in experimental astronomy: the study of exoplanets. Over the past few decades, this field has developed at an astonishing pace, revealing ever more secrets of alien worlds and demonstrating that our Solar System is just one of many planetary systems in the Universe, and not necessarily a unique one. Until now, however, all known exoplanets were found in systems gravitationally bound to their host stars, orbiting around them.

For many years, astronomers have realized that planets do not have to exist only in such bound systems. As a result of various processes, such as gravitational interactions with other planets during the formation of planetary systems or close flybys of neighboring stars, planets can be torn from their parent systems and ejected into interstellar space. These solitary planets, known as free-floating or rogue planets, then wander through the Milky Way without being tied to any star. Theoretical estimates suggest that their number could be very large, possibly even exceeding the number of planets bound to stars.

The idea of free-floating planets, and even the possibility that some form of life might exist on them, has fired the imagination not only of scientists, but also of science fiction writers. In recent years, many novels and film scripts have been set on such lonely, starless worlds drifting through the vast emptiness of the Milky Way.

But how can such planets be discovered and proven to exist if they do not emit light and do not interact with a parent star? The answer lies in gravitational microlensing, a technique that allows astronomers to measure the mass of an object that bends light. In practice, microlensing occurs when the light from a distant star is bent and amplified by the gravity of a closer object, called the lens. Because this effect does not depend on how bright the lens itself is, the method can detect dark, non-luminous bodies, even if the planet itself emits no light at all. The duration of a microlensing event generally depends on the mass of the lens. For objects with planetary masses, such events are very short, lasting only a few to several hours.

In 2017, astronomers from the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) project published results from a search for free-floating planets based on several years of intensive observations of about 50 million stars toward the Milky Way bulge. Among these, they discovered several thousand gravitational microlensing events with timescales ranging from hours to hundreds of days.

These observations indicated that free-floating planets should be quite numerous, but contrary to earlier claims, most of them should likely be low-mass planets rather than more massive, Jupiter-like ones, says Dr. Przemek Mróz, the first author of this groundbreaking study published in Nature.

Soon afterward, more promising candidates for free-floating planets were identified. Unfortunately, to directly determine a planet’s mass, astronomers need to know the distance to the lensing object. From Earth-based observations alone, this is possible only in exceptional and extremely rare cases. As a result, these objects remained candidates: depending on their unknown distance, their masses could be larger (even exceeding the range usually associated with planets) or smaller. Today, about a dozen such candidates are known. The least massive among them can have a mass as small as that of Mars. Nevertheless, despite being highly likely, the existence of free-floating planets had not yet been conclusively proven. No one had managed to directly measure the mass of such an object and confirm that it was truly a planet rather than a more massive body, such as a brown dwarf.

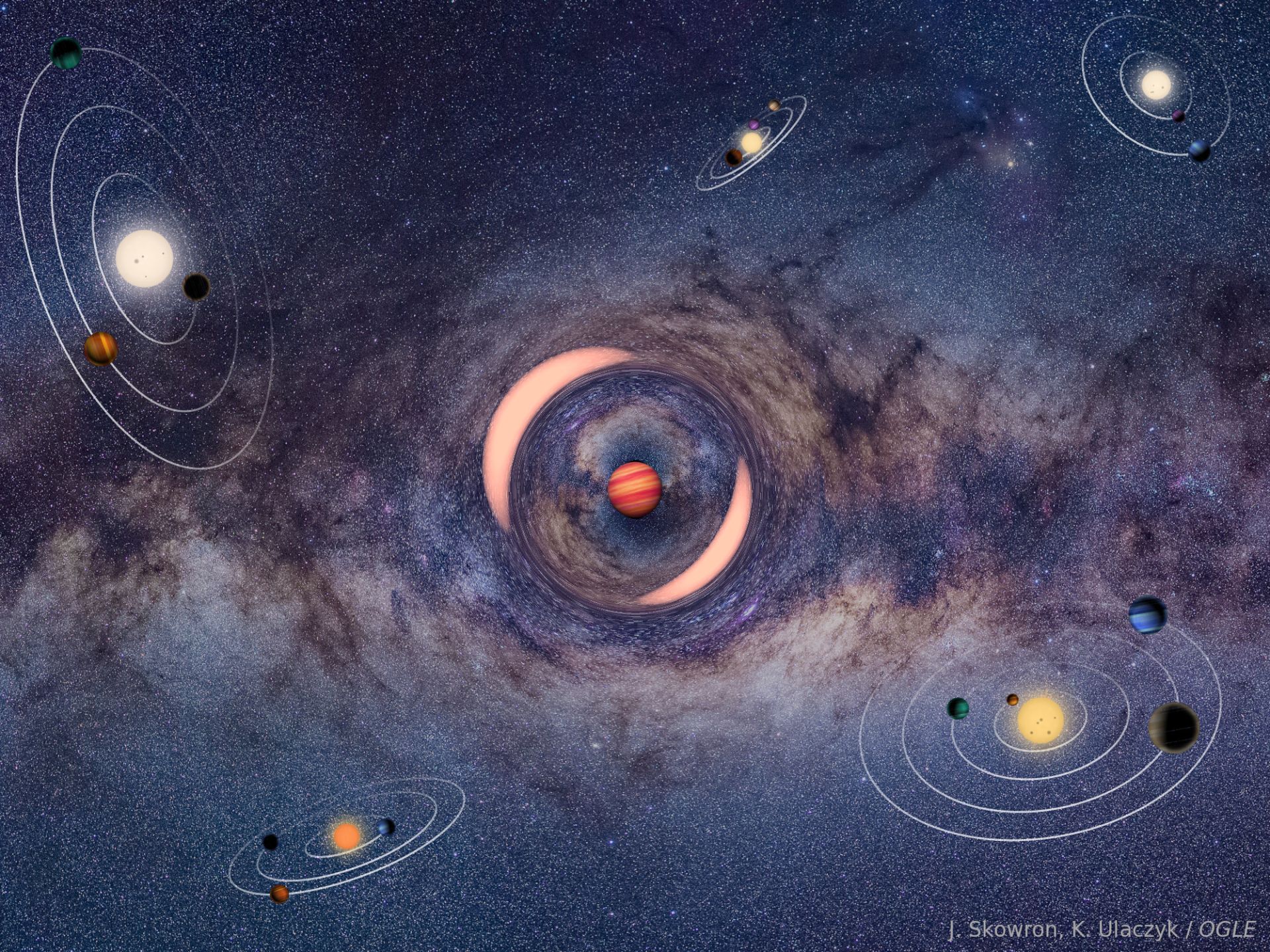

A free-floating planet gravitationally microlensing a distant star in the Galactic center. Two magnified images of the source star surround the Einstein ring of the event. All previously known planets orbit their host stars in gravitationally bound systems. Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE.

A breakthrough came with observations made on May 3, 2024. Using telescopes from the Korean KMTNet network (located in Australia, South Africa, and Chile), together with the OGLE telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, astronomers recorded a short-lived gravitational microlensing event involving a bright star near the center of the Galaxy. According to convention, the event was named KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516. Soon after the event ended, it became clear that the shape of the brightness variations matched predictions for microlensing caused by a free-floating planet. The event immediately joined the list of the most promising free-floating planet candidates.

A free-floating planet gravitationally microlensing a distant star in the Galactic center. Two magnified images of the source star surround the Einstein ring of the event. All previously known planets orbit their host stars in gravitationally bound systems. Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE.

A breakthrough came with observations made on May 3, 2024. Using telescopes from the Korean KMTNet network (located in Australia, South Africa, and Chile), together with the OGLE telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, astronomers recorded a short-lived gravitational microlensing event involving a bright star near the center of the Galaxy. According to convention, the event was named KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516. Soon after the event ended, it became clear that the shape of the brightness variations matched predictions for microlensing caused by a free-floating planet. The event immediately joined the list of the most promising free-floating planet candidates.

Astronomers soon realized that the region of the sky where this microlensing event occurred was being observed at the same time by the European Space Agency’s flagship mission, Gaia, which between 2014 and 2025 carried out regular photometric observations of about two billion stars across the entire sky. Gaia was not designed to observe very short-lived events, as it typically revisits the same region of the sky only every 30 days. Once again, however, extraordinary luck was on the astronomers’ side. Not only did the satellite observe this region during the brief, two-day-long event, but due to a particularly favorable orbital configuration, it collected as many as six photometric measurements within 15 hours, precisely during the most important moments, when the light amplification caused by the lensing object was strongest.

At that time, the Gaia satellite was located nearly two million kilometers from Earth, at the so-called L2 Lagrange point, a location especially well-suited for long-term astronomical observations from space. The simultaneous observations of the microlensing event KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 from Earth and from Gaia created a unique opportunity to measure the distance to the lens through the so-called microlensing parallax. The idea is similar to triangulation on Earth or to measuring distances to nearby celestial bodies by observing them from two different locations. Gaia’s photometric data were transmitted to Earth only in July 2024, at which point the Gaia Alert System team announced the event as an alert named Gaia24cdn.

An analysis of the microlensing data collected from the ground by the KMTNet and OGLE telescopes, together with the space-based data from Gaia, showed that the overall shape of the event as seen from both observatories, separated by about two million kilometers, was similar. However, the event recorded by Gaia occurred about two hours later than the one seen from Earth. This time shift made it possible to precisely determine the distance to the lensing object and the parameters of the microlensing event, which in turn allowed a direct and accurate measurement of its mass. The result showed that the object has a planetary mass of about 0.22 Jupiter masses, i.e., 70 Earth masses – slightly smaller than the mass of Saturn in our own Solar System. No evidence was found for the presence of a possible host star within more than 20 astronomical units (the Earth–Sun distance) of the planet. With very high confidence, the newly discovered object can therefore be considered unbound to any star - it is the first precisely “weighed” free-floating planet.

The discovery and direct mass measurement of a free-floating planet marks a major breakthrough in exoplanet research. It represents the first fully documented detection of an entirely new category of exoplanets: a vast and previously unexplored population of planetary objects whose study is essential for a complete understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve.

This is the discovery of the decade, comparable to the discovery of the first well-documented exoplanets in the 1990s, says Prof. Andrzej Udalski, leader of the OGLE project and corresponding author of the Science paper. Astronomers can finally be sure that objects of this kind really exist in the Universe.

The discovery of the first free-floating planet will undoubtedly provide a strong impetus for further intensive research on this class of objects. As early as 2026, NASA’s Roman Space Telescope mission is scheduled for launch, with the detection and study of free-floating planets as one of its main goals. During this mission, many such objects are expected to be discovered and characterized, allowing their properties to be studied in detail. Another upcoming mission is the Chinese Earth 2.0 satellite, planned for launch in 2028, which will also search for free-floating planets. There is therefore a strong chance that within just a few years we will know how numerous these lonely planetary wanderers of the Milky Way truly are.

Paper presenting results of these studies appeared on January 1, 2026 in Science.

The research conducted by Polish astronomers in the OGLE project is co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the National Science Centre and the Foundation for Polish Science. As part of earlier work, an international team of scientists published papers about cold super-Earths, common low-mass exoplanets orbiting their host stars at large distances, and drew up the first accurate three-dimensional map of the Milky Way.