16 January 2024

The National Science Centre (“NCN”), in cooperation with the CHIST-ERA network, hereby launches a call for international research projects in the following areas of:

- Multidimensional Geographic Information Systems (MultiGIS)

- Smart Contracts for Digital Transformation Ecosystems (SmartC)

Funding proposals may be submitted international consortia composed of at least three research teams from at least three participating countries. Standard consortium size: Three to six partners.

The principal investigator of the Polish research team must hold at least a PhD degree.

Participating countries:

Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Lithuania, Latvia, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, United Kingdom.

The application procedure:

- International level: joint proposals are drafted by Polish research teams in cooperation with the foreign partners (in English) and submitted to the electronic submission system of the CHIST-ERA network (ESS)

- National level: NCN proposals concerning the Polish part of the project are drafted by Polish research teams and submitted to the NCN electronically via the OSF submission system within 7 days of the date by which joint proposals must be submitted at international level.

PLEASE NOTE: This is a single-stage call which means that only full joint proposals are submitted at international level. More on the application procedure at international level can be found in the Call Text available on the website of the CHIST-ERA network.

Call Timeline:

- Submission deadline for joint proposals in ESS: 10 April 2024, 17:00 CEST

- Submission deadline for NCN proposals in OSF: 17 April 2024

- Call results: October 2024

- Project start date: December 2024

Under the CHIST-ERA Call 2023, funds can be applied for to cover salaries for members of the research team, salaries and scholarships for students and PhD students, purchase or manufacturing of research equipment and other costs crucial to the research project.

The total funding allocated by the NCN for research tasks to be performed by the Polish research teams under the call is 500 000 EUR.

Please read:

- the call documents available at https://www.chistera.eu/ (for all applicants in the call);

- information for applicants below and all annexes hereto (only for researchers applying for NCN funding).

Show all»

Hide all«

Proposals in the call may be submitted by the following entities specified in the Act on the National Science Centre (NCN):

- universities;

- federations of science and HE entities;

- research institutes of the Polish Academy of Sciences operating pursuant to the Act on the Polish Academy of Sciences of 30 April 2010 (Journal of Laws of 2020, item 1796, as amended);

- research institutes operating pursuant to the Act on Research Institutes of 30 April 2010 (Journal of Laws of 2020, item 1383, as amended);

- international research institutes established pursuant to other acts and acting in the Republic of Poland;

5a. Łukasiewicz Centre operating pursuant to the Act on the Łukasiewicz Research Network of 21 February 2019 (Journal of Laws 2020, item 2098);

5b. institutes operating within the Łukasiewicz Research Network;

- Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences;

- other entities involved in research independently on a continuous basis;

- groups of entities (at least two entities mentioned in sections 1-7 or at least one institution as such together with at least one company);

- scientific and industrial centres laid down in the Act on Research Centres of 30 April 2010 (Journal of Laws of 2020, item 1383, as amended);

- research centres of the Polish Academy of Sciences laid down in the Act on the Polish Academy of Sciences of 30 April 2010 (Journal of Laws of 2020, item 1796);

- scientific libraries;

- companies operating as R&D centres laid down in the Act on certain forms of support for innovation activities of 30 May 2008 (Journal of Laws of 2021, item 706);

- legal entities with registered office in Poland;

13a. President of the Central Office of Measures;

- natural persons and

- companies conducting research in other organisational form than set forth in sections 1-13a.

If research projects are carried out by at least two Polish entities applying for NCN funding, they must set up a group of entities (see item 8 above) and as such submit NCN proposals. An NCN proposal is submitted by a leader specified in the research project cooperation agreement concluded by the group of entities. An entity employing the principal investigator acts as the leader of the group of entities.

If, pursuant to Article 27 (1) (2) of the NCN Act, Polish entities cannot set up groups of entities, they are not eligible to apply for NCN funding of a joint research project.

PLEASE NOTE: Under CHIST-ERA Call 2023, funding proposals may be submitted by applicants for which funding of a research project will not constitute state aid, see NCN Council Resolution No 113/2023 of 7 December 2023.

The call covers the following subjects:

- Multidimensional Geographic Information Systems (MultiGIS)

- Smart Contracts for Digital Transformation Ecosystems (SmartC)

More information on the subject of the call can be found in the CHIST-ERA Call Text.

Polish researchers may apply for NCN funding of their basic research projects.

NCN proposals comprising research tasks overlapping with research tasks to be carried out in another proposal that has been already submitted in an NCN call may only be submitted once the evaluation or appeal concerning the earlier proposal has been concluded to the effect other than granting funding.

Research projects may be planned in the call for a period of either 24 or 36 months.

Apart from the principal investigator, research tasks in research projects may be performed by co-investigators, including students and PhD students as well as post-docs.

A post-doc type post is a full-time post designated by the principal investigator for a person who has been awarded a PhD degree in the year of employment in the project or within 7 years before 1 January of the year of employment in the project. This period may be extended pursuant to the Types of costs in research projects funded by the National Science Centre.

PLEASE NOTE: A post-doc position may be occupied by a person who has been awarded a PhD degree by another entity than the one planning to employ him/her at this post or has completed a continuous and evidenced post-doctoral fellowship of at least 10 months in another entity than the participating entity and in another country than the one in which he/she have been awarded a PhD degree. A prospective post-doc must be selected in an open call.

PhD students receiving NCN scholarships for research must be selected in an open call.

Scholarship grantees and post-docs must not be named in joint proposals or NCN proposals.

The rationale for involvement of individual members of the research team in the project shall be evaluated by an international expert team. The project must include the description of competencies and tasks to be performed by individual members of the research team.

To find out more on the budget for salaries and scholarships, read the Types of costs in research projects funded by the National Science Centre under international calls carried out as multilateral collaboration UNISONO.

The terms of the call do not specify the maximum number of research team members.

We recommend that Polish applicants should consult the budget table of the Polish part of the project (see the Budget Table of the Polish research team) with the NCN. The budget table in .xlsx format should be sent to alicja.dylag@ncn.gov.pl by 29 March 2024.

Creating a project budget is one of the most important aspects in the project planning which aims at identifying the required resources and estimating the costs required to perform the research tasks. The project budget must be based on realistic calculations and must comply with the guidelines laid down in the Types of costs in research projects funded by the National Science Centre within the multilateral collaboration UNISONO. The maximum budget of the Polish research team is not pre-determined; however, the rationale of expenses versus the scope of tasks is assessed by an international expert team.

The budget in NCN proposals must be quoted in PLN, while the budget in the joint proposal, in EUR.

The EUR budget for the Polish part of the research project in the joint proposal must be calculated according to the following exchange rate: 1 EUR = 4.5329 PLN.

The project budget (eligible costs) includes direct and indirect costs.

Direct costs include:

- remuneration:

- full-time employment: funds for full-time employment of the principal investigator or post-doc(s);

- additional remuneration for members of the research team. If the principal investigator is not intending to be employed full-time in the project, his/her remuneration is paid from the pool allocated for additional remuneration;

- salaries and scholarships for students and PhD students;

- purchase or manufacturing of research equipment, devices and software;

- purchase of materials and small equipment;

- outsourcing;

- business trips, visits and consultations;

- compensation for collective investigators;

- other costs crucial to the project which comply with the Types of costs in research projects funded by the National Science Centre under international calls carried out as multilateral collaboration UNISONO.

PLEASE NOTE: The costs of publication of monographs resulting from research projects, as defined in §10 of the Regulation on evaluation of the quality of research activity issued by the Minister of Science and Higher Education on 22 February 2019 (Journal of Laws of 2019, item 392) are not eligible until positively reviewed by the NCN.

Indirect costs include:

- indirect cost of Open Access (up to 2% of direct costs) that may be designated only for the cost of open access to publications or research data;

- other indirect costs (up to 20% of direct costs) that may be spent on costs that are related indirectly to the research project, including the cost of open access to publications and research data. During the project performance, the participating entity shall arrange with the principal investigator for the distribution of at least 25 per cent of the indirect costs’ value.

PLEASE NOTE: The cost of open access to publications may only be incurred as indirect costs. The cost of open access planned as direct costs will be regarded ineligible.

If unreasonable costs are planned, a proposal may be rejected.

Together with other European cOAlition agencies, the National Science Centre has drafted its Open Access Policy. In accordance with its vision of open access to research results and publications, the NCN requires that all research results should be made available in immediate open access. In accordance with the principles of Plan S, the National Science Centre recognises the following publication routes as compliant with its open access policy:

- publication in open access journals and on open access platforms registered, or with pending registration, in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ);

- publication in subscription journals (hybrid journals[1]), as long as the Version of Record (VoR[2]) or the Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM[3]) is published, by the author or publisher, in an open repository immediately upon the article’s online publication;

- publication in journals covered by an open access licence within the framework of the so-called transformative agreements, inscribed in the Efficiency and Standards for Article Charges registry (ESAC-registry).

Publication in transformative journals (TJ[4]). Transformative journals must meet the criteria laid down in the Guidelines on the Implementation of Plan S and must allow open access publication of original scientific articles. This publication route (3) only applies to articles accepted for publication or published before 31 December 2024.

Manuscripts must be published using the CC-BY licence (in the case of transformative journals, the CC-BY-SA licence can also be used). The CC-BY-ND licence may also be used (regardless of the publication route selected).

Please read the Open Access Instructions.

In grant agreements concluded after 1 January 2021, the data underpinning the scientific publications resulting from the project funded by the NCN must be well-documented pursuant to the FAIR Principles standing for machine or manual Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability or Reusability (the so-called “FAIR Data”). Where possible, data must be made available in the repository, according to the Creative Commons Public Domain (CC0 licence[5]). The data citation principles laid down in the Declaration of Data Citation Principles by FORCE 11 and the TOP Guidelines must be complied with. Metadata describing the data sets must be in line with the OpenAIRE.

[1] A hybrid journal is a subscription journal in which some of the articles are open access and some require payment of a publication fee.

[2] VoR is a version of record published in a journal with its own typeface and branding. Other terms: published version or publisher’s pdf.

[3] AAM is the final manuscript version created by the author, including all the revisions introduced after the peer review, and accepted for publication in the journal. Other terms: post print, accepted author manuscript.

[5] CC0 licence is a licence that allows the distribution of data to public domain. Pursuant to the licence, authors can give up their intellectual property rights to the extend allowed by domestic law; the licence does not affect patent rights, rights of publicity or privacy.

State aid must not be requested under CHIST-ERA Call 2023 .

For more information, please go to the State aid rules.

Joint proposals are subject to an eligibility check performed by the NCN, other members of the CHIST-ERA network participating in the call and the CHIST-ERA Call Secretariat.

Joint proposals deemed eligible are subject a to merit-based evaluation carried out by an international expert team pursuant to the Call Text.

NCN proposals are subject solely to an NCN eligibility check carried out by the coordinators.

The eligibility check of NCN proposals includes verification of proposals for completeness, compliance with the call documents and Resolution No 32/2023 adopted by the NCN Council on 16 March 2023, including compliance of the budget with an Annex to the Resolution (“Costs in research projects funded by the National Science Centre in international calls carried out as multilateral collaboration UNISONO”).

PLEASE NOTE: The information provided in NCN proposals and in joint proposals must be consistent and joint proposals annexed to NCN proposals must be the same as joint proposals submitted at international level.

Only joint proposals are subject to a merit-based evaluation which is performed by an international expert team established jointly by the members of the CHIST-ERA network participating in the call. To find out more on the evaluation of proposals, please go to the call text available on the website of the CHIST-ERA network.

The CHIST-ERA Call 2023 is expected to be concluded in October 2024.

Firstly, project coordinators will be notified of the outcome. Polish research teams will be notified by way of decisions of the NCN Director.

In the event of a breach of the call procedure or other formal infringements related to actions performed by the NCN, applicants may lodge an appeal against the decision of the NCN Director with the Committee of Appeals of the NCN Council.

For more information on the call, please go to the website of the CHIST-ERA network. For the terms and regulations on awarding NCN funding in the call, please refer to the Annex to NCN Council Resolution No 32/2023.

Should you have any more questions or queries, please contact us by e-mail or by phone:

If you are intending to submit a proposal to the CHIST-ERA Call, please:

- read all call documents, in particular:

- CHIST-ERA Call Text available on the website of the CHIST-ERA network;

- terms of and regulations on awarding funding for research tasks funded or co-funded under international calls launched by the National Science Centre and carried out as multilateral collaboration UNISONO;

Before submitting an NCN proposal to the NCN at national level:

- collect the data from the applicant that is required to complete the proposal and find out about the internal procedures that may affect the proposal and project performance (project costs, procedure for acquiring signature(s) of authorised representative(s) of the institution to confirm submission of the proposal); if the proposal is submitted by a group of Polish entities, draw up a research project cooperation agreement,

- make sure that the information in and annexes to the proposal are correct. Checking the proposal for completeness in the OSF submission system with the Sprawdź kompletność [Check completeness] button does not guarantee that the information entered is correct and the required annexes have been attached;

- check if the tabs have been completed in the correct language;

- disable the final version of the proposal to the NCN; and

- download the confirmation of proposal submission which must be signed by the principal investigator and authorised representative(s) of the institution.

Once the proposal has been completed and required annexes have been attached, the proposal shall be submitted to the NCN electronically via the OSF submission system using the Wyślij do NCN [Send to NCN] button.

Once the call for proposals has been closed:

- evaluation of proposals shall be carried out;

- if the proposal is recommended for funding, a funding agreement shall be entered into;

- the project shall be carried out pursuant to the funding agreement and Regulations on awarding funding for research tasks funded or co-funded under international calls launched by the National Science Centre and carried out as multilateral collaboration UNISONO.

In the event of a breach of the call procedure or other formal infringements, the applicant may appeal against the decision of the NCN Director with the Committee of Appeals of the NCN Council. The appeal shall be lodged within 14 days of the effective delivery of the decision.

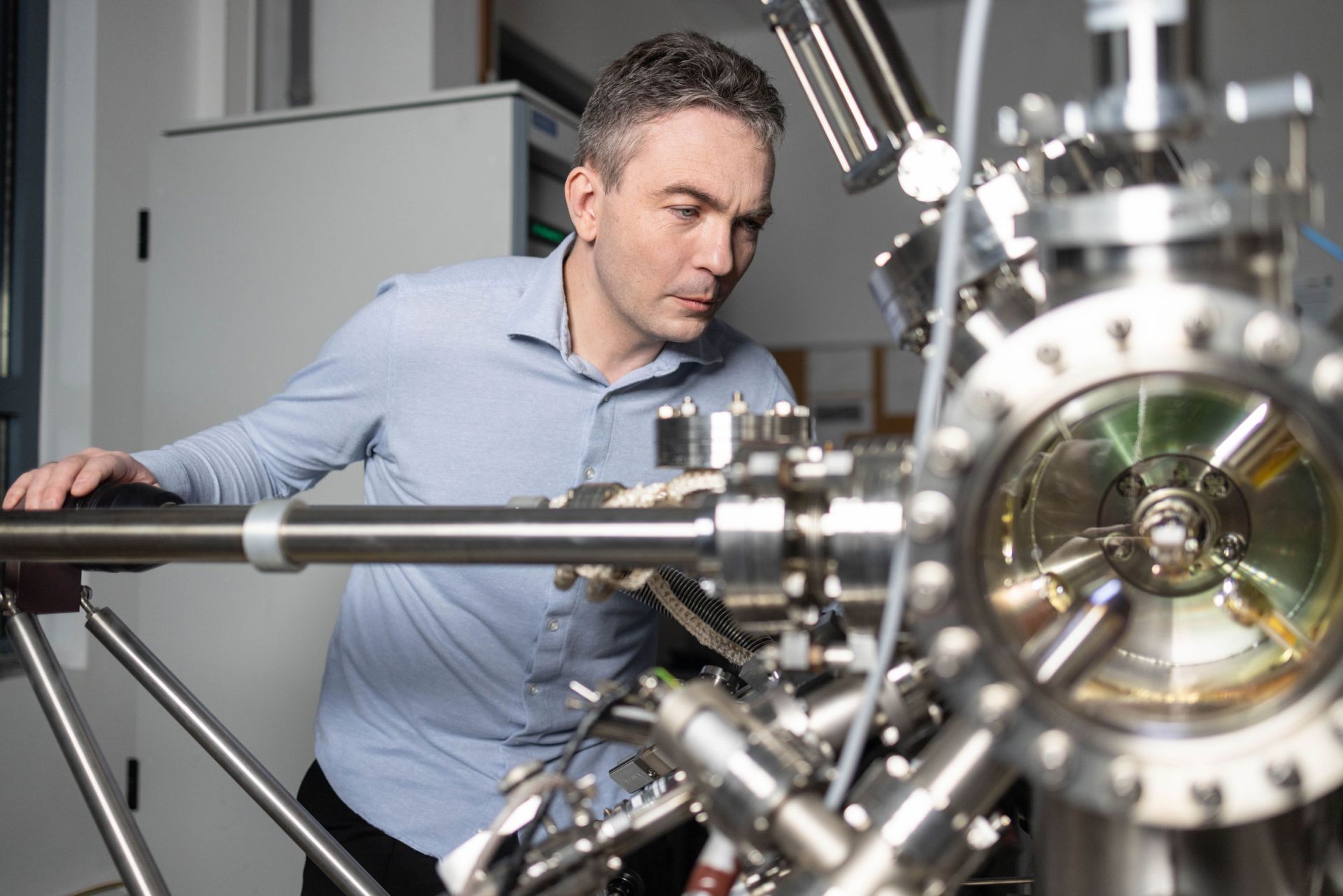

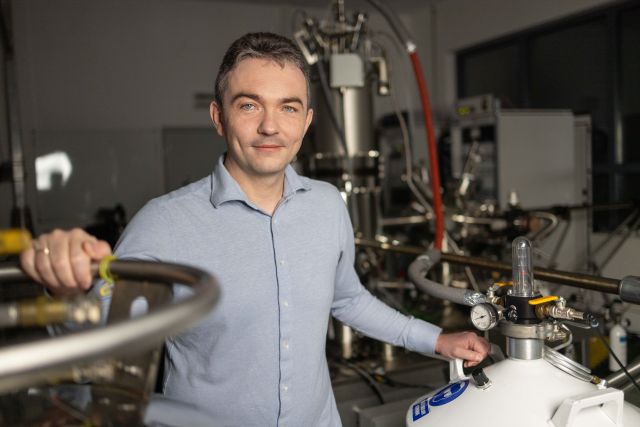

Prof. Magdalena Wrembel, photo by Michał Łepecki

The goal of the project is to investigate the complexity of third or additional language acquisition across different linguistic domains such as the sound system (phonology), grammar (syntax) and meaning (semantics). The project aims to explore the sources and directions of influence between language systems coexisting in multilingual speakers. The investigations compare learners acquiring their third/additional language in a naturalistic manner with those learning it formally in an instructed setting, taking into consideration varying levels of language proficiency (initial vs. advanced). Study participants include different groups of multilingual speakers who have Polish, English and Norwegian in their language repertoires and vary with respect to where and when they have learnt their non-native languages. A series of studies has been conducted in parallel in Poland and in Norway involving the participants’ all three languages. Experimental tasks include, among others, a range of production and perception tests, grammaticality judgment tests, sociophonetic interviews as well as online methods with the application of electroencephalography (EEG).

Prof. Magdalena Wrembel, photo by Michał Łepecki

The goal of the project is to investigate the complexity of third or additional language acquisition across different linguistic domains such as the sound system (phonology), grammar (syntax) and meaning (semantics). The project aims to explore the sources and directions of influence between language systems coexisting in multilingual speakers. The investigations compare learners acquiring their third/additional language in a naturalistic manner with those learning it formally in an instructed setting, taking into consideration varying levels of language proficiency (initial vs. advanced). Study participants include different groups of multilingual speakers who have Polish, English and Norwegian in their language repertoires and vary with respect to where and when they have learnt their non-native languages. A series of studies has been conducted in parallel in Poland and in Norway involving the participants’ all three languages. Experimental tasks include, among others, a range of production and perception tests, grammaticality judgment tests, sociophonetic interviews as well as online methods with the application of electroencephalography (EEG). Prof. Magdalena Wrembel, photo by Michał Łepecki

The project is innovative as it has an unprecedented broad scope, it is interdisciplinary and applies cutting-edge technologies alongside a range of more traditional research methods. It is based on a close international co-operation between active research groups from three renowned European universities (i.e., Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø and The Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim), with each partner institution specializing in one of the selected linguistic domains. The project provides comprehensive research on a complex topic that is currently very significant to the research community and to the general public. The project offers a research program and methodological design that may be further developed and extended by other researchers in the field. It broadens the current state of knowledge in this field which is relevant for policy-makers, educators, parents of multilingual children, and the society in general.

Prof. Magdalena Wrembel, photo by Michał Łepecki

The project is innovative as it has an unprecedented broad scope, it is interdisciplinary and applies cutting-edge technologies alongside a range of more traditional research methods. It is based on a close international co-operation between active research groups from three renowned European universities (i.e., Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø and The Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim), with each partner institution specializing in one of the selected linguistic domains. The project provides comprehensive research on a complex topic that is currently very significant to the research community and to the general public. The project offers a research program and methodological design that may be further developed and extended by other researchers in the field. It broadens the current state of knowledge in this field which is relevant for policy-makers, educators, parents of multilingual children, and the society in general.

Who may apply for NCN funding?

Who may apply for NCN funding? Who may act as a principal investigator?

Who may act as a principal investigator? What are the topics covered by the call?

What are the topics covered by the call? What is the project duration?

What is the project duration? What are the positions for members of the research team?

What are the positions for members of the research team? How should the budget be planned?

How should the budget be planned? Open access publication of research results

Open access publication of research results Can proposals in this call include application for state aid?

Can proposals in this call include application for state aid? What is the proposal evaluation procedure?

What is the proposal evaluation procedure? Who performs the merit-based evaluation of proposals?

Who performs the merit-based evaluation of proposals? When and how will the results be announced?

When and how will the results be announced? Where can additional information be found?

Where can additional information be found? Useful information

Useful information